The Egyptians: Early Chemists at Work?

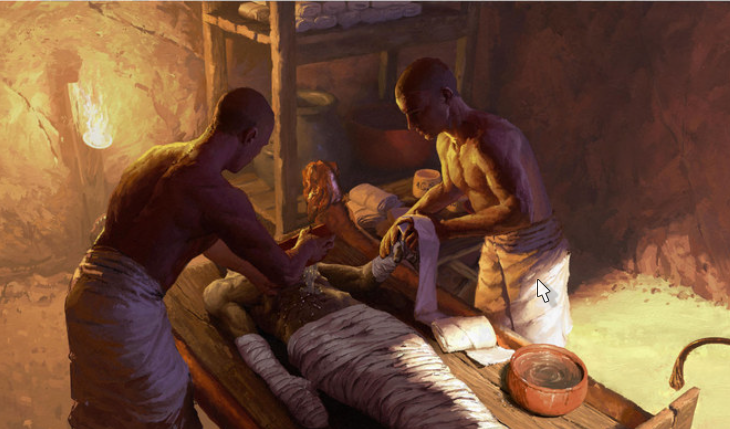

It’s easy to think of chemistry as a modern science, but the Egyptians were basically chemists without knowing it. Their whole embalming process was centered on one key goal—preventing decay—and they knew exactly which materials would do the trick. They perfected their techniques over centuries, transforming what could’ve been just a burial process into a sophisticated chemical procedure.

The mummification process itself is full of surprising chemistry that we still study today. Let’s break it down.

Step 1: Dehydration with Natron – Nature’s Drying Agent

One of the most important substances in Egyptian embalming was natron, a naturally occurring salt composed of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulfate. The body would be packed and covered with this compound to dehydrate it. By drawing out moisture, natron halted bacterial growth and decay, effectively “drying out” the body, a crucial step for long-term preservation. No moisture, no decay. Pretty clever, right?

If you’ve ever left a piece of fruit out in the sun and watched it shrivel up, you’ve seen a similar process at work. The difference here is that the Egyptians weren’t just drying bodies—they were preserving them so well that we can still see their features today.

Step 2: Removing the Organs – A Gruesome but Necessary Task

Now, here’s where things get a little… intense. The Egyptians understood that certain parts of the body, like the brain and internal organs, which decay quickly due to their high moisture content. The brain was extracted through the nostrils using a hooked tool, while the lungs, stomach, intestines, and liver were removed through a small incision and placed in canopic jars, each guarded by a deity. The heart, however, was typically left in the body as the Egyptians believed it was the seat of the soul.

Step 3: Antibacterial Oils and Resins – Nature’s Protective Shield

Once the body was dried and the organs removed, it was time for some natural antibacterial treatment. The Egyptians coated the body in a mixture of resins and oils, which were incredibly effective at keeping bacteria at bay. Frankincense, myrrh, and cedarwood oils weren’t just for ceremonies—they played a big role in keeping the body intact for the long haul.

Think of these oils and resins like a protective barrier. They helped seal the body from the elements and prevented microorganisms from causing decay. It’s kind of like putting an ancient antibacterial wrap around the body.

Step 4: Wrapping It All Up – Literally!

After all that careful preparation, the final step was wrapping the body in linen soaked with more of those protective resins. This wasn’t just for practical reasons—wrapping the body also had a deep spiritual significance. But from a chemistry perspective, those resins created an additional layer of protection, acting like an ancient form of plastic wrap that helped preserve the body from external moisture and bacteria.

By the end of this process, the Egyptians had created something truly extraordinary: a body that could stand the test of time, all thanks to their impressive knowledge of natural chemistry.

What Can We Learn from Egyptian Chemistry?

What blows my mind is how intuitive the Egyptians were about the science of preservation. Without any formal education in chemistry, they figured out how to use natural substances to achieve something that continues to fascinate us today. And when you think about it, we’re still using many of the same principles in modern preservation techniques. Isn’t it amazing how much we can learn from people who lived thousands of years ago? What’s even more astonishing is the long-lasting success of their techniques. Many mummies discovered today have retained skin, hair, and internal structures in surprisingly good condition, proving the effectiveness of their methods.

As we look back at this ancient civilization, it’s clear that chemistry has been at the heart of human progress for thousands of years, whether it was to preserve life—or in this case, to preserve it in death.